Co-teaching in higher education is quite new. In Europe, some universities have started with co-teaching in programs like social studies and mental health studies. Some countries and teaching institutions have more experience with co-teaching than others.

In the Erasmus+ project SEKEHE, some of the project participants have seen good results through several years. Others are still exploring the possibilities.

Sharing experiences across Europe

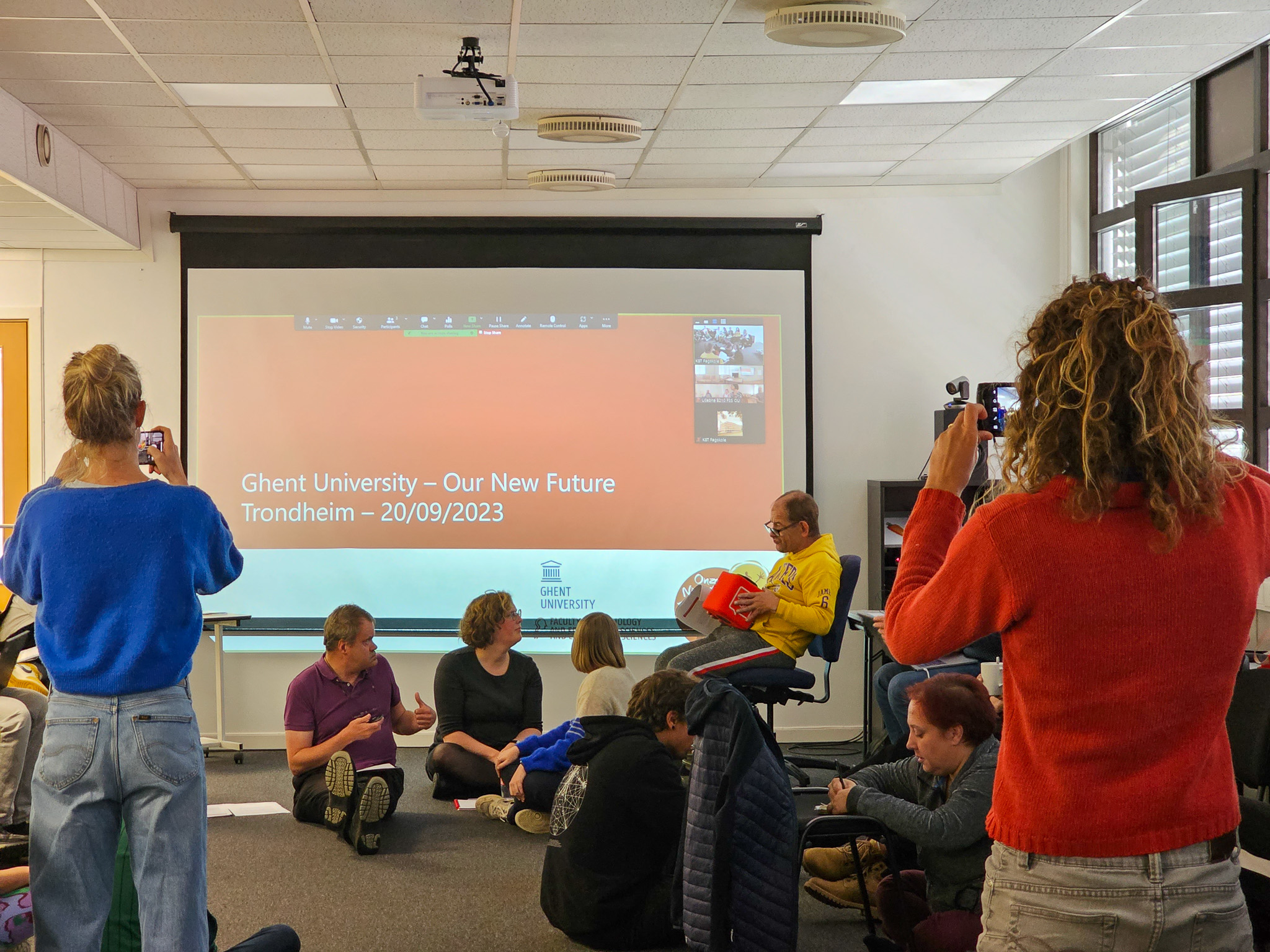

SEKEHE stands for “structural embedding of knowledge by experience in higher education through process of co-creation”. In September, the participants in the SEKEHE project had a meeting at KBT Vocational College in Trondheim.

One of the meeting activities was to share experiences of co-teaching. Even if the project participants had a shared perception of experiential knowledge earlier, the presentations led to an understanding that they still have a lot to learn from each other.

With project partners from 4 different countries, there is both cultural and linguistic differences to explore in the context of the project.

SEKEHE Project partners

- University of Ostrava (the Czech Republic)

- University of Applied Sciences and Arts, HOGENT (Belgium)

- Universiteit Ghent (Belgium)

- Universita’ Degli Studi Di Milano-Bicocca (Italy)

- NTNU (Norway)

- KBT Vocational College (Norway)

Learning of and about experts by experience

At the meeting in Trondheim, we took the opportunity to do a short interview with the project leaders, Jessica (Belgium) and Jakub (Czech Republic).

About the origin of the project, Jessica explained that she met a colleague of Jakub, Martin, at a conference about mental health, and the idea started in an informal way. At the conference, Jessica and Martin discovered that they were thinking a lot alike.

They started talking, and a friendship developed. More people got involved, and they started talking about how they were working with experts by experience. They then decided to write a project together on the topic, and invited other colleagues they were in touch with. The colleagues from Italy were also om a workshop at the conference where Jessica and Martin met. The group slowly grew, and then Ottar Ness from NTNU came in, and now here we are.

Discovered different contexts along the way

The SEKEHE project are now at the end of the first year. In the first work package, they have been sharing experience of co-teaching. How can they embed knowledge by experience in the courses that they give to their students? There have been different experiences in the different countries in the last year.

Jakub explain that they in this phase of the project, are realising there is difference in the context for the project partners. Now they are discussing what experiential knowledge really means. It can mean different things in different countries. They are still trying to find some kind of framework for describing this activity.

The project is a good arena for exploring the topic and inspire each other. Each country and institution are in different phases of developing this kind of work. In Italy they are just starting and in Ghent they already have a lot of experience.

In the output of the project, you can see experience from those who are just starting and those who have been developing it for many years.

Systems for support

Next year they are going to set up systems of support for students and finding out how they can embed knowledge by experience in those systems of support. They have started with a focus on the teaching, now they are shifting more to the support part. Jessica adds that there’s also a third layer of the project: Focusing on structurally embedding the knowledge by experience in the education. What should change in the universities and university colleges?

The final goal is to have inclusive education where knowledge by experience is a pillar besides the scientific and the professional knowledge.

Structural challenges in the universities

When asked about challenges of co-teaching at universities, Jessica points out that she have met some structural challenges. Not all experts by experience have a formal degree, and therefor they have requested some flexibility from people at the HR department. Also, they need to honour them properly for the work they are doing.

On the level of cooperating with other lecturers, Jessica tells us it’s taking time to create a common ground where people are aware of the benefits of co-teaching. They have to make opportunities to speak about doubts. Is this a good idea? Should we do this? “It’s important to create this openness!”, she says. “This is something we are going to do, and this is the way to go. Without this openness, you lose half of the people before you even started.”

Self-stigma

On the question “Have you met any stigma in this project?”, Jessica says:

“The last two days, some of the experts by experience have been talking about self-stigma. It’s partly in how the organization structure in education is organized. They sometimes feel less as an expert by experience in the current system, because you really have to fight to get your position there as an expert by experience. It’s often only seen as an added value, but not a necessity. They were talking about self-stigma, but it is also somehow created by how the education system is organized. “

Jakub continues: “That’s a big part of some of their stories. It can depend on the stage of their life. Some told that they have met stigmatizing reflections from their students. The students want to bring something into it, and may not be reflecting about the labels, that some of their experience is stigmatizing.

This is an important moment where they can open a discussion. The teachers and the co-teachers try to not judge the students when bringing up something stigmatizing, but to open up a discussion about it. It’s also a difficult situation that brings in insecurities. It’s something we have to look more into, how to work with stigmatization in this teaching process.”

Reducing stigma by openness

Jessica says she think it also takes stigma away in some way. “Because when we started with the co-teaching, we see that the students are suddenly much more open to talk about their own vulnerabilities. It’s some kind of a catalysator: “Ah! It’s okay to talk about these things”. Without this, this openness wouldn’t happen. It’s another way of interacting and creating a dialogue. So, by doing that it’s also breaking stigma. Because all of the sudden subjects are much easier to talk about. It goes in both directions.

It also brings challenges, because all of a sudden, students bring up a lot of issues they’re confronted with. And you see a lot of colleagues thinking: “Ouf! What now? What do we have to do with it?” It’s still an insecurity there with professionals and lecturers. “What’s our role in this? If we break the stigma, somethings come up, and what then? “ ”

Why is a project like SEKEHE important?

There are many layers of why this project is important. Jakub says: “One of them is to give a value of this kind of practise in an institution, because it’s kind of connected to the project. It brings more visibility in the institutions. Even the colleagues that are not involved, or were not interested before, now see that its more power in it. It’s covered by something international.

It’s also a lot of inspiration across context, that we have seen during the workshops. The enthusiasm of people coming here, hearing and seeing that they are not alone in this. That they can connect and that they have friends around in Europe.

Also, the level of creating some robust justification and the ground for how to describe this kind of thing. So, it’s not just an addition to the ways of how we are teaching and learning, but as a core thing in the context.”

Jessica continues: “I think it’s good if it can be a way in how to support inclusive education. In the end, all partners want that the education systems are open to everyone. And it’s in how you look at knowledge, by really embedding this knowledge by experience. But also, how can people in vulnerable situations be included in our education system as well.

It’s content wise, but also about transforming your education system. So that we don’t exclude people from our education system, and that we don’t start already with this excluding process in our own institutions. It’s a big aim, but maybe we can start with planting a seed with SEKEHE.”

Photo voice as method

During the SEKEHE project, all of the teams have been working with photo voice, where art meets research. They use photography to discuss certain topics that are relevant to the project.

Jessica says: “I think that’s an innovative way of working, which is also very useful if you want to have social impact and change. Because you will reach another audience than when you just write an article, or a paper or whatever.

It’s social change on that level, but it’s also another way of working with people. You work with them in the identity of a photographer, not someone with a background of mental health issues. You are working in this project in the role as a photographer, and what’s important for you. It’s a whole different way in how you look on how you work with people. You’re in an equal position. Because the lecturer is also working as a photographer to bring his or her story. I think this is something special in the SEKEHE project, that also unites us.

Maybe there can be an exhibition of the photos on the SEKEHE website. It can intrigue people in a different way by creating these kinds of material as well.”

About Jessica and Jakub

Jeccica is from Belgium. She works at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts, HOGENT in Ghent. There she is a coordinator of the EQUALITY//Research Collective. That’s a research centre where they do practice based research, mostly in the social domain. Two important frames of references: Human rights and quality of life. Embedding knowledge by experience is one of the central pillars of the research centre.

Jakub is from the Czech Republic. He works at Ostrava University, Faculty of social science, educating social work. They focus on social work and bringing the experienced knowledge into the studying of social work. Also, they emphasis is on critical aspects of social work.

Jakub is involved in a project which invited people with specific experience to be a part of the educational process. They have experimented with this the last few years, even before the SEKEHE project started.

Last: What do you think about Trondheim?

Jakub: “I like it. Compared to where I live, it’s less cars. More green cars. With small kids, it’s good to experience a city where you can move more freely, with bikes and green areas. I like to have nature around and clear air. I would like to hike around. “

Jessica: “I was surprised that this is the third largest city in Norway. Went to the fortress and sent a picture to her boyfriend with the text: This is how a city could also look like.”